Imagine for a moment that you are Penny Mordaunt. You hope to become Conservative leader. First, you must hold your own seat, Portsmouth North. Labour needs a swing of more than 17 per cent to defeat you. When YouGov published its mammoth poll last week, you were relieved that it reported a national swing of 15 per cent – not quite enough to turf you out.

But then you looked at the figures for Portsmouth North. YouGov projected a 20 per cent swing. Instead of becoming party leader, you would be out of parliament.

Mordaunt’s personal prospects reflect a deeper truth. This election looks set to overturn seven decades of political science. John Curtice says the Tories could lose 60 more seats than they would from the traditional way national vote shares translated into parliamentary seats – potentially turning a bad defeat into an existential catastrophe.

If so, the true comparison is not with Tony Blair’s landslide in 1997, it is with Winston Churchill’s humiliation in 1945, when the Tories lost more than 200 seats.

The reason flows from the latest evidence about the relationship between votes and seats. For decades, that relationship has been shaped by Uniform National Swing. UNS is based on the observation that most constituencies have broadly similar numbers of floating voters. This has meant that the swing in any particular seat is unaffected by whether it was safe Labour, safe Tory or marginal.

Recent large-scale polls that seek to project seat-by-seat results suggest that UNS no longer works. It’s not just that Tory support is low, and threatened by Nigel Farage’s impact now he is back in the fray. It is that voters seem especially determined to punish MPs such as Mordaunt who are defending apparently safe seats.

The detailed maths behind this analysis are complex, but the principle is simple. “MRP” polls build up a detailed picture of Britain’s electorate, and apply it to the demographic profile of each constituency. In the current election, they find that the more votes the Conservatives won last time, the more they will lose this time. Typically they reckon that a Conservative candidate defending a normally safe seat is suffering a 3,000 vote penalty, on top of the votes they are on course to lose from the general nationwide swing. Mordaunt, Sunak and their colleagues must hope that the MRP algorithms are wrong, and that UNS will triumph once again. Is that possible? By its nature, MRP tends to predict bigger swings in safer seats anyway. However, the evidence from last month’s local elections and non-MRP polling data confirm that UNS has stopped working

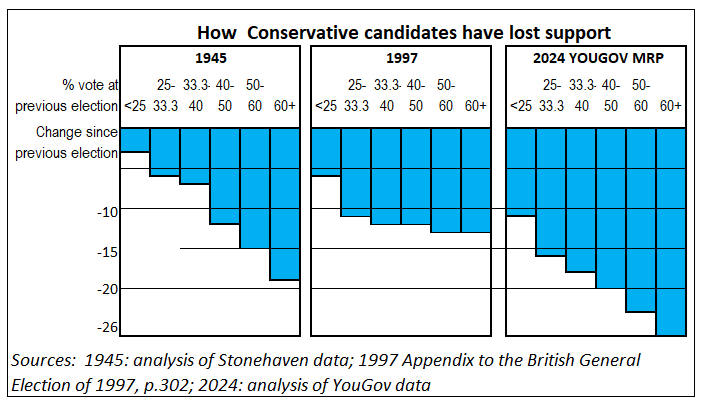

This adds to the Tories’ woes. Even in 1997 the Conservative base held firm. The figures for that election shown above were calculated by Curtice at the time. In line with the principles of UNS, he found “little difference between those seats where the Conservatives started off with just one-third of the vote, and those where they had previously won two-thirds”. The chart shows that this is not what is happening in this year’s election.

Nor is it what happened in 1945. Like 1997, but unlike any other post-war election, it saw the Conservatives lose more than half their seats. I had not seen an analysis of the pattern of swing in that election, so decided to check the numbers. I was surprised by what I found. As the chart shows, the 1945 pattern was nothing like 1997, but uncannily close to current MRP polling.

Sunak should be terrified by the 1945 precedent. The Tories suffered badly from losing lost most votes in their strongest areas. Clement Attlee’s Labour party won a 146 majority with a 10 per cent lead in the popular vote. On a uniform swing, its majority would have been halved.

Labour was destined to win the 1945 election anyway. It was because of the pattern of the swing that the Conservatives were unable to prevent a landslide. This year, they need to break that pattern. Can Sunak succeed where Churchill failed?

His one glimmer of hope is that many of his missing voters have not transferred their allegiance to another party. Instead they tell pollsters they don’t know how they would vote. There are up to three million of them. Another two-to-three million say they will vote Reform. If the Tories can woo the ex-Tory undecideds and counter Farage’s appeal, then maybe they can do more than see their vote share rise. It’s just possible that UNS will revive and Tory candidates will avoid the MRP penalty that many of them currently face.

He should be warned, however, that although UNS has generally worked in post-war general elections, there are two recent exceptions. In 2015 Labour’s support in Scotland fell from 42 to 24 per cent – similar to the current polling story for the Tories. Seat by seat, the more votes Labour won in 2010, the more it shed in 2015. The party lost all but one of its 41 MPs.

In the same election, the Liberal Democrats’ Britain-wide vote slumped from 24 to 8 per cent. Again, the more votes they had won locally in 2010, the more they lost in 2015. They held only eight of their 57 seats.

Like the Lib Dems and Scottish Labour in 2015, the Tories are now are suffering not just an adverse swing of the electoral pendulum, but an existential haemorrhage of support. They are losing core supporters, not just floating voters. Their urgent need is to win back the undecideds and defectors to Reform. Otherwise their prospects are indeed bleak.

This analysis was first published in the Sunday Times