In the run-up to the Conservative conference, there has been much discussion about Richi Sunak’s core political beliefs. What does he really stand for? What kind of Britain does he wish to build? In short, what is Sunakism?

Perhaps we should ask a more basic question first: why should our Prime Minister have an “ism” at all? Thatcherism was, of course, a clear doctrine with a lasting impact. But we have had six Conservative Prime Ministers since the iron lady. Who – at the time or since – has talked without irony or rebuke of Majorism or Cameronism or Mayism or Johnsonism or Trussism? Type any of these terms into a computer and a squiggly red line appears, warning us that our PC does not recognise the word. “Cakeism” attracts no such warning. Boris Johnson’s self-defined political purpose – flippant and destructive – is the nearest we have to a generally recognised post-Thatcher “ism”.

So why have “Sunakism”? The practical answer is that after the divisions and collapse of the May premiership, the cavalier dishonesty of the Johnson years, and the catastrophic idiocies of the Truss weeks, Sunak needs to project a completely different brand image from those of his recent predecessors. The Telegraph, Mail and Spectator have all sought to define Sunakism. I can find no evidence of Downing Street warning its friends in the media to call off the quest.

The most prominent answer was supplied by the Daily Mail just before last Christmas. Six weeks after Sunak became Prime Minister he gave a long interview to his favourite cheerleader. The paper’s headline was: “So what is Sunakism? It’s peace of mind, lower taxes and a genuine pride in Britain.”

Sunak said: “What people want and deserve is peace of mind. Peace of mind that we are going to repair the economy, give them the support they need with energy bills and reducing the cost of living and make sure that they have good well-paid jobs. But peace of mind is also about knowing the public services like the NHS are going to be there for you and your family when you need them.”

Somewhere Karl Popper will be spinning in his grave. The celebrated philosopher gave us the Falsification Principle. He said that for a theory to have substance, it must be possible to set up a test that could prove it wrong. Finding a black swan disproves the statement that all swans are white.

Much the same applies to politics. An ism, or statement of purpose, has substance only if a sane rival can propose the opposite with a straight face. Thatcher passed the Popper test with flying blue colours. She wanted to curb the trade unions, sell council homes and privatise the great public utilities. Labour opposed all these things. One of the truisms of the 1980s was, “whether we like Thatcher or not, we know where she stands”.

Let’s apply the Popper test to Sunak. Which of these things would Labour, or any party, reject: peace of mind? “Repair the economy”? Help with energy bills? Lower cost of living? Well-paid jobs? The NHS available when we need it? All six are things that all politicians want all the time. Applying the falsification test, Popper would undoubtedly not just have failed them but wondered why Sunak bothered to offer such motherhood-and-apple-pie ambitions at all.

Observant readers may have noticed something missing from Sunak’s six-part list: lower taxes. It’s there in the Mail’s headline. Isn’t this something that would divide the parties at a time when public services are so short of money? Here’s the thing. The word “tax” appears nowhere in the 1,637 word interview feature. He reveals how he cooks his Christmas turkey (“I am big on brining, and also goose fat for the roast potatoes”), but not how he would help workers keep more of the money they earn. Now it’s possible that he made his ambitions clear, but his commitment was deleted by incompetent editing. Is that likely? Many criticisms are made of the Daily Mail, but sloppy editing is seldom one of them.

The reality, of course, is that Sunak cannot cut taxes just now. Given the weakness of the economy and the size of the Government’s deficit, he has to be cautious. Indeed, caution is his constant motif. Given the mess he inherited from Truss, he is right to be careful. His problem is that caution, laced with right-wing instincts, seems to be his only cause. if there is a Sunakism, safety-first is its weakly beating heart. It’s an ism, Jim, but not as we know it.

Consider the evidence. On Brexit, he has rejected the closer relationship with Brussels sought by much of British business. We have seen sensible steps forward on the Northern Ireland Protocol and the Horizon science programme – but nothing to address the mammoth cost of losing frictionless trade with our biggest export market. He is sacrificing jobs and prosperity to his Brexiters.

On climate change he says he is sticking to the target of net zero by 2050, while breaking the promises he inherited, and initially embraced, to reduce our carbon emissions significantly within the next ten years. He is dressing up short-term electioneering and a concession to his right-wing as long-term vision.

And so on. Caution is not always wrong; boldness is not always right. But Sunak’s caution carries a political as well as economic risk. If Sunak is to eschew inspiration and principle in his quest for votes, he must rely on his general reputation for getting things done. That means leading a government that is seen as competent, trustworthy and in touch – what political scientists call “valence” virtues that often decide the choices of floating voters at election time.

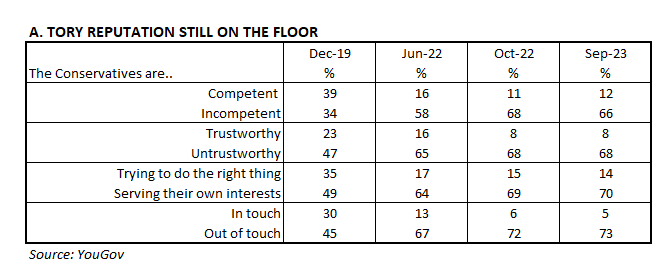

The news is not good. Sunak’s latest YouGov rating is his worst yet: minus 45 (23 per cent view him favourably. 68 per cent unfavourably). He has completely failed to rescue his party from the melodrama of Boris Johnson’s resignation and the catastrophe of Truss’s premiership. Table A tells the story. Immediately following Johnson’s big victory in 2019, the Conservatives had a middling reputation – not much trusted, but reasonably competent. This would not normally be good enough to produce a landslide, but the Tories are not normally up against a leader as unpopular as Jeremy Corbyn.

By June 2022, in the run-up to Johnson’s resignation, the party’s image was dreadful. Well under 20 per cent of the public regarded the Tories as competent, trustworthy, in touch or “trying to do the right thing”. In each case, between 58 and 67 per cent thought the opposite. So Conservative MPs deposed him, and party members chose Truss to succeed him. Following the mayhem of her mini-budget and the sharp rise in interest rates, the party’s ratings sank further into the mire.

In the steady, pragmatic hands of Sunak, they would surely recover? No they haven’t. His party’s reputation is just as bad as it was during the darkest days of Truss’s premiership – and worse than when Johnson’s premiership hit the rocks.

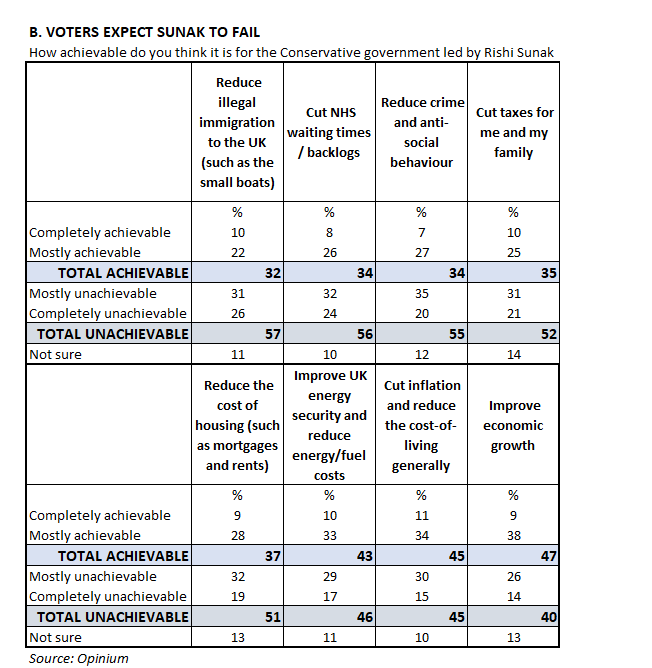

Could things now improve? Sunak plainly hopes they will, when he manages to…. repeat after me… halve inflation, create better jobs, reduce the national debt, cut NHS waiting lists and stop the boats. His problem is not just that most of his targets look likely to be missed, but that having touted them so firmly and so often, any failure will be doubly painful. Not only will he have failed to make things better; he will have broken specific promises.

More broadly, Opinium’s latest poll for The Observer finds that voters are generally sceptical about what Sunak will achieve. It tested eight issues, including four of Sunak’s five targets. As Table B shows, on only one, improving economic growth do more people say they are “achievable” rather than “unachievable”. Just one in three voters say that reducing immigration, taxes, crime or NHS waiting times is achievable under a Sunak-led government. (Actually, crime has steadily fallen for the last two decades, but most voters think it has risen; one of the truths of electioneering is that, where they differ, perception trumps reality.)

Where, then, does this leave Sunakism? He lacks both a distinctive ideology and the capacity to inspire. He leads a party that is regarded just as badly as it was when Sunak put on his bright sheriff’s badge and rode into town to clean it up. Maybe his best option is to abandon all isms and persuade his media cheerleaders to forget the notion.

However, if he still wants one attribute, even if not a full ism, that could help him in the months ahead, Sunak should heed the advice of Joe Klein. He is the shrewd American journalist who was outed as the “anonymous” author three decades ago of Primary Colours, a fictional version of Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign to become President.

At the time, the holy grail for politicians craving public respect was thought to be authenticity. Be yourself, they were told. Voters like politicians who say what they really think. When I discussed this with Klein, he doubted its effect. Authenticity, he said, was too easy to fake. Good politicians need a quality that has to be genuine.

Such as? I asked. I offer to Sunak, and any other politician seeking votes, the answer Klein gave me: “courage”.

This analysis was first published by The New European